Yes, we live in the most peaceful time in history. Most humans are able to go outside without the fear of getting killed. At least at the time of the writing.

I understand the risk of war, and even of a world war, has increased over the last decade, but we're still nowhere near the levels of conflict that plagued humanity before 1945. The fact that military service has stopped being mandatory in many countries also speaks volumes.

Has there ever been peace in the world?

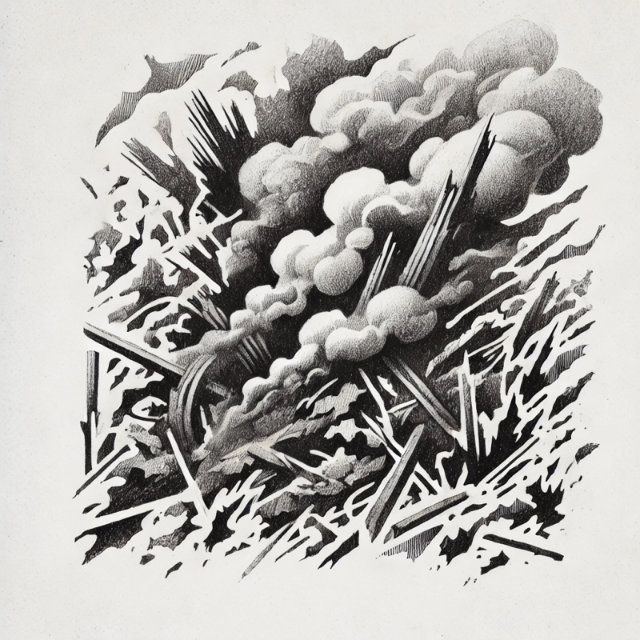

Even so, I'm curious to explore the idea of peace (or its absence) in a little more detail. The word war instantly conjures visions of atrocities and a persistent fear of death. That’s our first reaction, followed by emotions shaped by our culture, personality, risk tolerance, and family ties.

But let's stay on that first reaction—fear for safety, fear of death. I think this sums up beautifully our dread of war—the fact we, as well as our loved ones, may lose our lives. That war is a period when we stop being safe.

But has there ever been a time in our history (or pre-history even) when we felt extensively and comprehensively safe from organised and armed group aggression?

There's evidence of humans engaging in conflicts as early as pre-historic times, long before ideas common to modern warfare were even invented, such as the nation, the motherland, freedom, organised religion and such things. Nevertheless, early human conflicts led to the same feelings of dread the modern version is so good at producing.

The ludicrous idea that, in order to be safe, one needs to go to war; and that peace can only be achieved with victory in war, appears to have its roots in the attack is the best form of defence attitude, in turn based on the prehistoric practice of raiding. That was when a kin group (extended family) engaged in aggression against a neighbouring group to take their resources, and did it in a way that minimised their own losses and maximised their benefits.

Hunter-gatherer groups didn't realise at that time that, by ambushing their neighbour and destroying it, taking their resources and even their females, they were changing the world forever and making it primarily an unsafe place for everyone—themselves included.

Modern ethnographic studies of tribal communities confirm that intertribal violence often involves low-risk attacks, killing a few of the target group, capturing women, but taking low casualties. Among aboriginal Australians, regular lethal conflict [...] was conducted through dawn raids, ambushes, or nighttime skirmishes, ways that limited the prospect of loss to the attacker.

— Why War, Richard Overy, 2024

Now, if you were wondering, like me, if there ever was a time in our existence when we lived safely from dread of being killed, raped or maimed, the answer seems to be no.

Animal war

As ludicrous as we may be, our species isn't the only one specialised in killing each other. In fact, running for one's life is a behavioural trait common to most animals. Perhaps we know it better by the terms fight or flight, first popularised by the American physiologist Walter B. Cannon in the early 1900s.

And as humans, we have become much more sophisticated at surviving conflict, not just by running away, but also by putting up a good defence.

Yet defence supposes a certain level of preparedness where a group of people actively prepare against a conflict that hadn't yet occurred and where the enemy may not even be known yet. Anyone, except members of the same group, could be the enemy. They could be just outside the camp, looking for an easy target, ready to hit, ready to ambush when least expected.

Of course this takes us to us-versus-them and stranger paranoia, something that's so deeply engrained we're still teaching our children to not talk to strangers. And while that might be good advice, the encroaching paranoia that comes with it is where I can see the seed of conflict and war.

We build walls, fashion sophisticated weapons and train our young men (and even women) so that when (not if) war comes, we are prepared. And the key here has become the sophistication of our weapons, ever increasing, driven by the fear of our enemies having still better weapons.

Although rooted in the same anguish, we have gone beyond the simple animal war.

For we fight not against flesh and blood

I’ve often wondered how people manage to wage war, knowing the “enemy” is as human as they are. Entire nations don’t choose to go to war—rather, their leaders decide for them.

1914 Christmas Truce

For a long time, the story if the 1914 Christmas Truce was the only war story I could believe or identify with.

At Christmas 1914, hundreds of soldiers stopped fighting one another, left their trenches and shook hands in no man’s land. For several days, even weeks, British and German soldiers in Flanders barely fired a shot, helped bury one another’s dead, and even played football together.

—Understanding the 1914 Christmas Truce, Simon Jones

But by the Second World War, it’s nearly impossible to imagine the Nazis fraternizing with their enemies. Even if they had tried, would British or American soldiers have joined them on a football field? The perception of “the enemy” was radically different. During World War I, many soldiers weren’t entirely sure why they were fighting; by World War II, Nazi ideology was so abhorrent that soldiers preferred to die rather than surrender.

Suddenly, war seems more justified: not merely to satisfy someone’s urge to steal and dominate, but to combat an evil so great that people are willing to risk everything. Psychopaths alone can’t fight these battles; they must rally others, often with ideology and propaganda.

Hitler argued his people were the supreme human race and it was their duty to ensure it didn't get polluted by vermin. Others alike spun the truth into lies or imaginary tales of doom, from jihad to crusades when everyone's soul was in peril and its salvation came only by fighting the devils across the trenches. We all owe it, to the fatherland, the saviour, god or freedom, we all need to die so the psychopaths get their hit.

Yet there is more to war than raiders and defenders. Lines between good and bad are blurred and lofty ideals that once seemed worth dying for may no longer ring true to the people of the future. We can't simply rock, paper, scissors although I really wished that we could. We are, even as we dread it, the product of conflict and the sons and daughters of those who won it (or at least managed to survive it long enough).

Recommended Reading

Understanding why humans go to war is a complex topic and if you'd like to go more in depth, I recommend Why War? by Richard Overy (2024).